Development in Progress

The concept of progress is at the heart of humanity’s story. | Jul 16, 2024

In an information war, it is essential to be able to distinguish education from propaganda. Unfortunately, it is not always easy. Today’s citizens are swamped with manipulative information, and often crave truly educational environments that they can trust. In this, the second paper of our series on information warfare, we argue that propaganda can be thought of as the “evil twin” of education. They often look the same, but with some careful examination, their differences become apparent. Exploring the historical dynamics of propaganda and considering its various forms helps us understand the telltale signs of coercive, manipulative, and propagandistic information. Understanding the difference between propaganda and education, and how complicated the distinction can be at times, allows for better situational awareness. Clarity about the difference allows us to protect both ourselves and our communities from being casualties of the information war. This is an essential step toward creating a healthier epistemic commons for everyone.

As the information war continues to escalate, it is getting harder to create the cultural equivalent of “demilitarized zones” in which non-weaponized communication can take place. Education[1] can often use the same technologies and even deliver some of the same content and ideas as propaganda. The critical difference, however, is that education is—by design and intention—non-coercive, non-manipulative, and anti-propagandistic.

Like relationships between teacher and student, or parent and child, educational relationships are reciprocal and open-ended. There is a mutual interest in decreasing asymmetries of knowledge and power over time. A good teacher wants their student to be able to know the material at least as well as they do. Both parties desire graduation, or growing into maturity.

Educational relationships are intrinsic to culture, civilization, and human identity. Relationships that allow for intergenerational transmission of complex skills, values, and ideas are a species-specific trait unique to homo sapiens. They cannot benignly be replaced by propagandistic relationships or other modes of social control in which one group exercises power over another. It is not possible to graduate from a propaganda campaign into a position of knowing as much as the propagandizers. This is one of several structural differences between education and propaganda.

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) celebrates its 100th anniversary, there has been a global spectacle of related propaganda. This has included news events, political speeches, parades, and multimedia initiatives, such as those unfolding around the cinematic production of the movie 1921.[2] The narrative recounts the history of communism in China, leaving the viewer with no sense that communism has done any wrong in Asia. It has broken box office records in China already and is being rolled out for international release. Themes raised in the movie have created a national discussion within China—a conversation the CCP is seeking to expand to the whole world.

What has come to be called propaganda has a history as long as the history of civilization.

The film has been called propaganda explicitly by the U.S. media, as it sits nestled within a symbolic field of activity created around the CCP centennial celebrations. Other examples include Xi Jinping giving a speech in Tiananmen Square wearing a jacket almost identical to those worn by Mao. The U.S. media’s coverage of the CCP centennial has been controversial, because of what has been seen by some as a laudatory tone—or at least a conspicuous absence of criticism regarding the overt propaganda.

But how does this CCP propaganda differ from U.S. celebrations of national pride, such as the recent presidential inauguration, or the repeated theatrical remembrances of 1776? Why is it reasonable to label the CCP celebrations propaganda, but not similar celebrations in the United States? Within the U.S. and other countries that hold elections, supporters of political parties will often see the “other side” as using propaganda to secure votes, while considering their own side as running a clean campaign. People tend to see the trusted news sources of their in-group as educational, and the other side’s news sources as propaganda.

What has come to be called propaganda has a history as long as the history of civilization. The term itself first appears in the heading of a 16th-century papal bull critiquing Protestantism. This public decree issued by Pope Leo X accused the proponents of the Reformation of using a kind of black magic to propagate their ideas.[3] Pope Leo X was waging a propaganda war against Luther, using the arts in particular—St. Peter’s Basilica was finished as part of these efforts. Luther himself was a master propagandist—The Ninety-Five Theses can be read as exemplary propaganda. Shortly thereafter, the 17th century marked a major watershed in the development of propaganda, as widespread adoption of the printing press allowed for a range of new techniques and impacts.[4]

The history of propaganda began before the printing press.

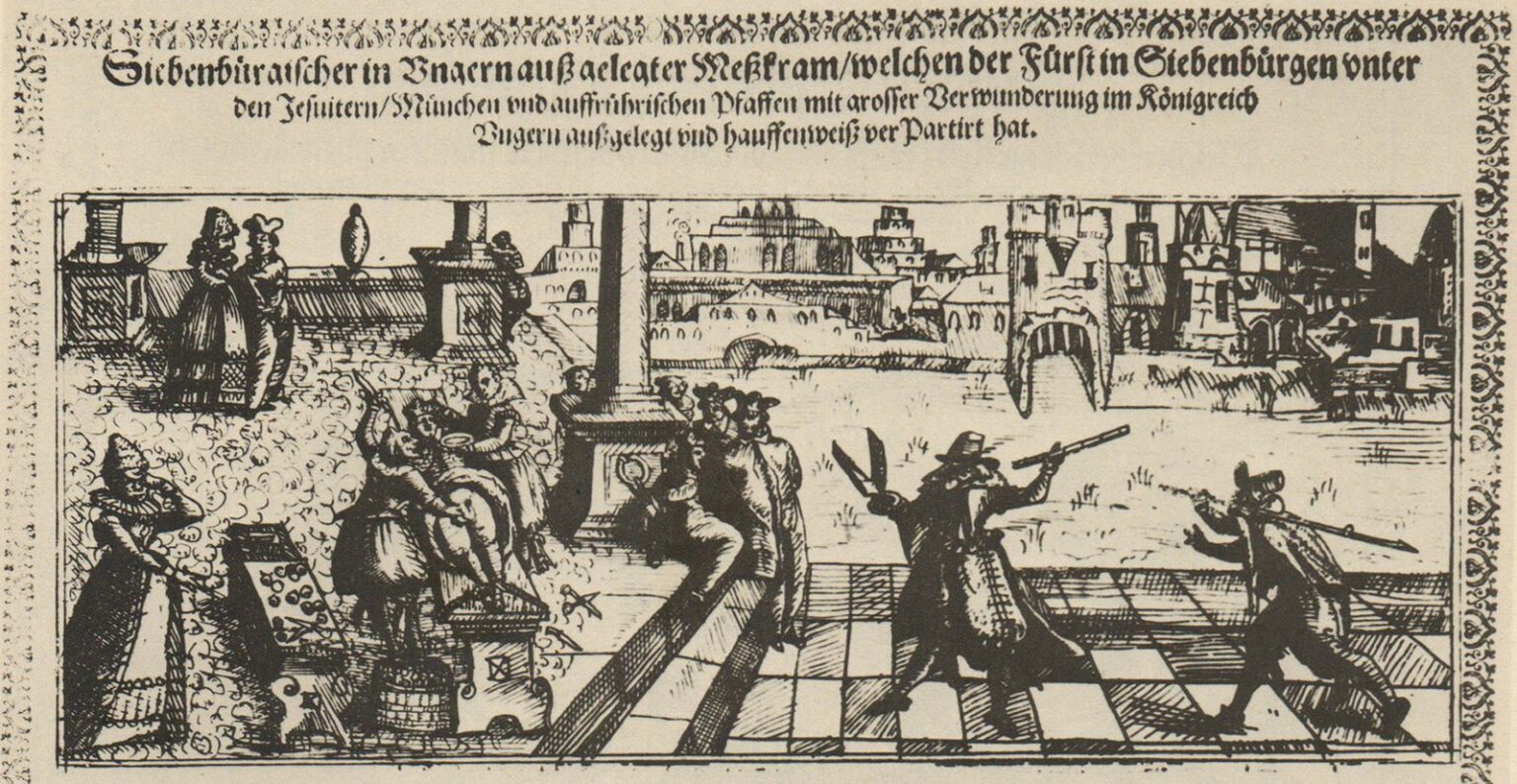

Catholic propaganda poster c. 1620, distributed in Germany and Transylvania. The images show the prince of Transylvania (a leading Protestant) in an open air garden castrating Jesuits. A barber approaches with shears and a measuring rod, followed by a soldier. Captions below (not pictured) explained these events to those who could read. These events never occurred. Image from Elmer Palmer, Propaganda in Germany During the Thirty Years War.[5]

During the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), tens of thousands of propaganda pamphlets and posters were printed and distributed, many of which were made up of impressive and provocative images that were aimed at the illiterate.[6] Concepts of hell, heaven, and salvation were weaponized. Choosing sides in the ideological battle was cast by propagandists as a choice between greater or lesser forms of eternal damnation. In one poster, we see an artist’s rendering of a well-known and identifiable political leader conversing with the devil, who is himself in the process of castrating monks from a nearby city. This kind of propaganda artwork had major impacts on its target populations, comprised largely of poor and illiterate peasants. For the literate and emerging bourgeois classes on the other hand, entire books of propagandistic theology relied on the Bible and philosophy to justify total religious war.[7]

In the 17th century, we find many familiar features of “modern propaganda.” Posters and leaflets flooded cities and agitated urban populations into violence through coordinated mass communication. Common tactics emerged, including the propagation of fictional atrocities to demonize enemy populations. There was covert publication of forged or leaked documents with false authorship. Pandemics and the concept of “the Plague” were used to villainize populations associated with its spread. Finally, and perhaps most profoundly, religious leaders leveraged the power of the arts and theology to manipulate human emotions.

But the history of propaganda began before the printing press. Monuments, murals, sculptures, architecture, coinage, and control of the written word have been a perennial means of demonstrating power and exerting political influence. Egyptian pharaohs (Ramses II and IV) and Roman emperors (Julius Caesar, Augustus, and Trajan) had complex propaganda operations as a key aspect of their governance, although they did not call them by that name. Archeological evidence suggests these practices have occurred in all human civilizations on all continents for millennia.[8]

This use of human symbolic capacity as a means of social control at scale is distinct from (yet emergent out of) the use of spoken language to pass on skills, values, and other essential forms of knowledge and practice.[9] Using media such as sculptures, manuscripts, and symbolic events to exert political control over a large population was a fundamental innovation, which has allowed for the vast size and scope of human social coordination.[10] This innovation in propaganda coexisted with the use of those same media for the purposes of passing on (and often improving) knowledge, skills, and capacity.

The race between propaganda and education determines the life course of a civilization—and importantly, the timing of its demise. So significant is the problem of propaganda that careful theoretical and scientific work has been undertaken to understand its nature and morphology, including the way it grows, evolves, and transforms as an aspect of arms races in information war. Propaganda is being defined and redefined continually as the field of information warfare evolves.

A great deal depends on what is meant by the word propaganda. Institutions as divergent as the New York Times (NYT) and Fox News can both be seen as producing different kinds of propaganda. Moreover, propaganda must be understood as distinct from related phenomena, such as disinformation, conspiracy theories, fake news, and other features of our damaged information commons. Propaganda and advertising are also distinct, as we explore below.

In the first piece of this series, the term irregular warfare was defined as the broadest category of strategic and tactical conflict beyond munitions and physical violence. One form of irregular warfare is information warfare, although there are also various kinds of economic and political warfare. Information warfare may be categorized further to include espionage, psychological warfare, and a whole range of various kinds of propaganda. Since the First World War, propaganda has been a field of academic study, and a range of definitions has been created.[11] We suggest a multi-faceted definition that begins with the following sentence:

It should be noted that the same definition can be applied to advertising. However, in advertising the focus is on economics, not politics: advertising is any media product that has been deliberately designed and distributed by or for an economic group, such as a company, in order to influence consumer behavior. The distinction between the economic and the political is tenuous at best, so some theorists include most forms of advertising as a sub-class of propaganda. This approach is justifiable, as long as careful attention is paid to the distinction between commodity purchasing and political action as the respective goals of advertising and propaganda. Of course, education differs from both, as we discuss later in this paper.

The table below presents an overview of the implications of propaganda as defined above. A feature of the many forms of propaganda is that it is possible to accuse others of using it, while at the same time denying that you are using it yourself. It is possible to switch subtly between different meanings and uses in the practice of propaganda. Our definition, in conjunction with the table below, seeks to synthesize those that have been offered in the field over many decades.[12]

A key implication of this analysis of different types of propaganda is that modern information warfare is not primarily about spreading lies—although it certainly does involve lying in some cases. As we documented in the first paper of this series, the emerging academic field of computational propaganda is concerned with documenting and critiquing the efforts of governments and militaries who use troll armies to create disinformation environments that confuse and agitate whole populations. But that is only the most obvious form of propaganda today.

Propaganda also works by means of known legacy institutions distributing many partial truths across all possible communication platforms over extended time scales, sometimes lasting decades. Modern propaganda is not primarily about manipulating people to believe sensational and foolish things. It is about playing the long game, and slowly changing people’s underlying worldviews, dispositions, and habitual behaviors in the direction desired by those waging the campaign.

One of the reasons for the normalization of propagandistic communication techniques is longstanding confusion about the difference between propaganda and education.

Classic strategies for changing people’s minds include shaping research agendas in specific sciences in particular directions.[20] This could, for example, entail creating a specific kind of research institute tasked with asking only a certain, pre-defined set of questions. The results of this research are spread through multi-media advertising campaigns, frequently orchestrated by public relations firms. These firms now use experts in psychometrics to target specific ads to specific personality types, based on user data lifted from social media sites. The firms collaborate with think tanks and academics to create publications, which are repackaged in relationships with the media and onto every screen. After some time—it could be months or years—large segments of the targeted population have changed basic habits and beliefs, while now making choices that conform with the interests of those controlling the information environment.

One of the reasons for the normalization of propagandistic communication techniques is longstanding confusion about the difference between propaganda and education. A common perspective is that the “good guys” use communications science to create media for information and education, while the “bad guys” use manipulative psychological tactics to create propaganda and lies. If the media product is created by our in-group to spread our message, then it is not propaganda, irrespective of clearly propagandistic strategies of communication. On the other hand, anything containing political ideas at odds with those of our in-group is labeled as propaganda, even if it has all the markings of good faith educational communication.

It is easy to mistake the difference between propaganda and education as depending on the content of the message being conveyed, rather than the techniques, intentions, and effects of its conveyance. As all sides create propaganda of various kinds, they also accuse others of doing so and deny it themselves. In heavily propagandized environments it can become hard to tease apart agreeable propaganda from information that is truly educational. Those seeking in good faith to serve as educators become almost impossible to distinguish from those seeking to serve as culture warriors.

The months leading up to America’s entry into World War II mark another watershed in the history of propaganda. Hitler’s propaganda was historically unprecedented and unmatched by his rivals. It played a large part in his early military and political successes, and eventually it reached American shores. In October of 1939, German-American Bundists held a parade on East 86th Street in New York, in which hundreds of men in brown shirt uniforms marched with American flags, alongside others bearing the red, black, and white of Nazi swastikas. Later in February that same year, 22,000 Americans rallied in Madison Square Garden to support fascism. The staging was orchestrated to look like a Nazi rally, centered around a vast portrait of George Washington, flanked by long rectangular banners bearing the stars and stripes of the U.S. flag.[21]

All of this was of course particularly alarming to those who had come to America to escape the spread of fascist power in their own countries. Some of these emigres and refugees were intellectuals, artists, and journalists. These groups fell into collaboration with prominent American academics and political operators. In 1941, concerns about the need to combat Nazi propaganda and prepare Americans for another world war led to the creation of the Committee for National Morale. This largely forgotten organization played an essential role in the dynamics of information warfare during both World War II and the Cold War. Committee members were all highly influential members of the American academy and government, including the anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, as well as psychologists Gordon Alport and Harry Stack Sullivan.[22]

Historical records, including correspondence and organizational documentation, suggest the early members of this group were operating in good faith to avoid creating a mirror image of Nazi propaganda. They feared the U.S. could become an authoritarian regime by virtue of the structure of propagandized communication itself. Some sociologists feared that mass broadcast media such as radio and TV inevitably created authoritarian personality structures, because the rise of fascism correlated so strongly with the onset of these communications technologies.

Fascists effectively used radio, TV, film, and the press to create a personality open to authoritarian control. How could those same media be used to create a personality capable of participating in democracy during wartime? Mead and Bateson explicitly characterized this problem as concerning the difference between propaganda and education.[23]

Their focus was on the structure and uses of new communication technologies as instruments of either coercion and undue influence, or as instruments of education with the potential to empower democratic citizens. They were seeking to inspire a “species of scientific [information] management designed to simultaneously liberate and coordinate the actions of democratic selves.” In such a context, “Leaders needed to act like educators,” Bateson suggested, and they needed to teach people how to “learn to learn.”[24]

Mead’s and Bateson’s solution was to create fundamentally different kinds of media experiences, which arguably established large scale educational campaigns that transcended the category of propaganda, at least for a brief time. They worked to create non-coercive informational and artistic events in which participants were able to gain their own impression about essential ideological issues of the day. They were not told what to think, but rather given enough information of various kinds to decide for themselves. This radically new multimedia approach would eventually be repurposed during the Cold War by Eisenhower’s information warfare units, and later still by advertisement and cultural event producers. Therefore, the work of the Committee for National Morale cannot be taken as any kind of solution. Certain aspects of their work represent important forays into educational alternatives to large-scale propaganda (such as, for example, the controversial art photography exhibit, The Family of Man).[25]

The limitation of the approach adopted by the Committee on National Morale is that it was still a form of centralized technocratic control. Their methods were susceptible to cooptation and retrofitting by propagandists. People were free to explore any direction or aspect of the Committee’s rich multimedia exhibits and campaigns, but these experiences could only be chosen from a menu created by a small group of experts. This is sometimes called “choice architecture” and it is currently used as one aspect of “nudging” campaigns, in which certain personal decisions are mitigated through the careful control of choice architecture in information environments and commercial interactions. An increasingly common subject for these campaigns includes the many societal challenges around public health, such as smoking and obesity. The ethics of this form of social control are contested, despite the Obama administration’s major governmental initiatives towards the deployment of such strategies.[26]

Mead and Bateson misidentified the key issue as being about the structure of the communication environment: broadcast vs. multicast; didactic vs. interactive; little choice in what to watch vs. lots of viewing options. These are undoubtedly important factors in shaping our engagement with the information commons. The key difference, however, is really all about the dynamics of asymmetry in information and power. What is the relationship between those who hold knowledge and those who are in need of it? Is there an unbridgeable knowledge gap, by design, or is there a path toward mutual responsibility for the total range of knowledge (i.e., graduation)?

Both propaganda and education involve the deliberate design of informational environments, for the purposes of emotional engagement, behavior change, and the learning of specific ideas. As we have seen, propaganda acts ultimately in the interest of powers held by a political group. Education, however, acts in the interest of reducing the difference in power between those “in the know” and those who need to learn. Educators are interested in securing a successful transmission between generations and classes of shared responsibility for the social system. True educators are not interested in solidifying political power and administering social control through the use of information and its strategic communication.

Educational relationships always involve a situation of legitimate epistemic asymmetry: the teacher knows more than the student, and this is known and embraced by both parties. Educational media and practices—in schools and beyond—seek to lessen and eventually make obsolete the very asymmetry upon which the relationship is based. The goal is that the student graduates and does not need to be dependent upon a specific source of epistemic authority. They become one themselves. This means the educator is radically accountable and responsible for what they say and do because they are in a position that is by design creating an eventual peer—someone who can fully check and evaluate their work.

Groups seeking to educate whole populations on how to think and act need to take steps that show they are accountable for the impact of their influence.

Propaganda also usually involves an epistemic asymmetry: the propagandists know more than the propagandized, or at least act on that assumption. Propaganda works to maintain and widen the asymmetries of power and knowledge that make propaganda possible and apparently necessary. This is because the goal is to exercise control over the behavior of target populations, not to help them expand the range of their behavior into realms occupied by the propagandists—such as the realms of deciding what is “true” and “false.” As such, the propagandists, by design, cannot be held accountable for the content of their communications because they have disallowed the possibility.

The propagandists’ complete sources and data are simply never made accessible to the propagandized. A good teacher, though, will consider exactly the same text as their student and aim to pass on the responsibility for understanding all of the data and more. The contrast here is clear, but in practice it can be hard to detect.

A clear example can be drawn from the pharmaceutical industry. Drug companies have been known to conduct large scale “public health campaigns” to convince people that a drug is safe, despite never revealing all the data necessary to evaluate safety comprehensively.[27] In such cases, the information campaign is designed to influence behavior towards taking the drug, rather than to educate earnestly about the nature of the drug and the research behind it.

To be even more specific, in COVID-19 vaccination public health campaigns, there are at least two pieces of uncontested (though rarely stated) information that tip the balance away from education and towards propaganda. The first is that the raw data held by pharmaceutical companies is not available to anyone but them. Nor should it be, under current legal standards of practice for drug research. Nevertheless, this creates an unbridgeable epistemic asymmetry, and one that is actively guarded against breach.

The second is that vaccine manufacturers are not accountable for the failure of the vaccine to work or for the injuries caused by the vaccine. And again, according to the letter of the law, they are not required. However, this creates an anti-educational relationship between the company and its customers. How trustworthy can a teacher be who will not seek to be held accountable for their claims and recommendations? No teacher would do that; only a salesman would have that kind of fine print.

Groups seeking to educate whole populations on how to think and act need to take steps that show they are accountable for the impact of their influence. Not doing so undermines the possibility of learning because it generates a fundamental distrust. If unbridgeable epistemic asymmetries are established and maintained, while accountability is avoided, then it is hard not to receive the label of propaganda and deserve it.

Recent research shows that the most highly educated (those holding PhDs) are the most hesitant to take COVID-19 vaccines.[28] The least-educated are also among the most hesitant, although they are more likely to change their minds. At least part of the explanation for these findings are the discernable dysfunctions and unbridgeable epistemic asymmetries involved in public discourse about the vaccine. Only a few extra questions reveal that the possibilities for education are overrun by powerful propaganda. It is not a question of who presents “facts.” It is a question of who presents enough total information, alongside evidence of good faith and clarity of presentation, to allow a motivated and reasonable person to become truly educated about the topic. Is the creator of the message relating to us in good faith as potential students and collaborators, or in bad faith as if we are part of a target population to be manipulated? Although this is often difficult to establish, on occasion it can be crystal clear—particularly in the case of microtargeted advertisements and public service announcements appearing in a social media newsfeed.

Some want to build rubrics, checklists, and other analytical tools to empower citizens. The problem with simple “propaganda analysis tools”[29] is that they can’t keep up with the arms races taking place at the frontiers of information warfare. Moreover, once such a tool has been created, a sophisticated propagandist could use it as an objective reference to “prove” their work can be trusted. This kind of certification of “official truth” is part of the problem, and often functions as covert propaganda.

Indeed, the work of the Consilience Project risks being labeled as covert propaganda precisely because it claims to offer content that is only educational. Isn’t this exactly what good propaganda would claim? Isn’t this content propaganda too, especially because it is claiming not to be? These kinds of questions form a vicious cycle of epistemic suspicion—a form of epistemic nihilism—and removes the possibility for education to occur. It makes the mistake of assuming that there is no point in even trying to distinguish between education and propaganda. A cultural mood of epistemic nihilism is the fallout of information war. It leads to an inability to orient toward legitimate epistemic asymmetries. The end result is a breakdown of educational cooperation between generations. Over time, epistemic suspicion systematically distorts educational exchange—between generations and between parts of society with access to different levels of information.

Our recommendations here are based upon principled commitments, rather than concrete prescriptions, diagnostic techniques, or media literacy rubrics. All these measures are important and remain the focus of effort and inquiry by others. In our paper on the challenges of making sense of the 21st century, we discussed the need for a new ethos of learning and a new emotional stance of epistemic humility.[30] For these kinds of principled values to manifest there must also emerge new practices and cultural habits, and likely new kinds of institutions.

In the first paper of this series, we offered the idea of “combat free zones” or “demilitarized zones”: educational refuges in the context of a total and escalating information war. This is where the weapons of the culture war could be laid down so that a different form of communication could take place. However, only a prior shared commitment to an ethos of learning can enable this kind of ceasefire. The epistemic hubris and nihilism resulting from propaganda must be replaced by the good faith questioning and epistemic humility that drive cooperative educational engagements.

We know already the catastrophic outcomes of mismanaged educational crises, and the dire consequences for open societies in particular.[31] It is clear that one of the main challenges to securing viable futures for open societies is limiting the range of propagandistic communication. If we let propaganda continue to dominate and shape our information commons, the future will be determined by an ever-smaller group of powerful interests. In that scenario eventually it is everyone who bears the catastrophic cost of humanity’s self-imposed inability to make sense of the world.[32]

The noun was coined by the American ecological psychologist James J. Gibson. It was initially used in the study of animal-environment interaction and has also been used in the study of human-technology interaction. An affordance is an available use or purpose of a thing or an entity. For example, a couch affords being sat on, a microwave button affords being pressed, and a social media platform has an affordance of letting users share with each other.

Agent provocateur translates to “inciting incident” in French. It is used to reference individuals who attempt to persuade another individual or group to partake in a crime or rash behavior or to implicate them in such acts. This is done to defame, delegitimize, or criminalize the target. For example, starting a conflict at a peaceful protest or attempting to implicate a political figure in a crime.

Ideological polarization is generated as a side-effect of content recommendation algorithms optimizing for user engagement and advertising revenues. These algorithms will upregulate content that reinforces existing views and filters out countervailing information because this has been proven to drive time on-site. The result is an increasingly polarized perspective founded on a biased information landscape.

To “cherry pick” when making an argument is to selectively present evidence that supports one’s position or desired outcome, while ignoring or omitting any contradicting evidence.

The ethical behavior exhibited by individuals in service of bettering their communities and their state, sometimes foregoing personal gain for the pursuit of a greater good for all. In contrast to other sets of moral virtues, civic virtue refers specifically to standards of behavior in the context of citizens participating in governance or civil society. What constitutes civic virtue has evolved over time and may differ across political philosophies. For example, in modern-day democracies, civic virtue includes values such as guaranteeing all citizens the right to vote, and freedom of culture, race, sex, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, or gender identity. A shared understanding of civic virtue among the populace is integral to the stability of a just political system, and waning civic virtue may result in disengagement from collective responsibilities, noncompliance with the rule of law, a breakdown in trust between individuals and the state, and degradation of the intergenerational process of passing on civic virtues.

Closed societies restrict the free exchange of information and public discourse, as well as impose top down decisions on their populus. Unlike the open communications and dissenting views that characterize open societies, closed societies promote opaque governance and prevent public opposition that might be found in free and open discourse.

A general term for collective resources in which every participant of the collective has an equal interest. Prominent examples are air, nature, culture, and the quality of our shared sensemaking basis or information commons.

The cognitive bias of 1) exclusively seeking or recalling evidence in support of one's current beliefs or values, 2) interpreting ambiguous information in favor of one’s beliefs or values, and 3) ignoring any contrary information. This bias is especially strong when the issues in question are particularly important to one's identity.

In science and history, consilience is the principle that evidence from independent, unrelated sources can “converge” on strong conclusions. That is, when multiple sources of evidence are in agreement, the conclusion can be very strong even when none of the individual sources of evidence is significantly so on its own.

While “The Enlightenment” was a specific instantiation of cultural enlightenment in 18th-century Europe, cultural enlightenment is a more general process that has occurred multiple times in history, in many different cultures. When a culture goes through a period of increasing reflectivity on itself it is undergoing cultural enlightenment. This period of reflectivity brings about the awareness required for a culture to reimagine its institutions from a new perspective. Similarly, “The Renaissance” refers to a specific period in Europe while the process of a cultural renaissance has occurred elsewhere. A cultural renaissance is more general than (and may precede) an enlightenment, as it describes a period of renewed interest in a particular topic.

A deep fake is a digitally-altered (via AI) recording of a person for the purpose of political propaganda, sexual objectification, defamation, or parody. They are progressively becoming more indistinguishable from reality to an untrained eye.

Empiricism is a philosophical theory that states that knowledge is derived from sensory experiences and relies heavily on scientific evidence to arrive at a body of truth. English philosopher John Locke proposed that rather than being born with innate ideas or principles, man’s life begins as a “blank slate” and only through his senses is he able to develop his mind and understand the world.

It is both the public spaces (e.g., town hall, Twitter) and private spaces where people come together to pursue a mutual understanding of issues critical to their society, and the collection of norms, systems, and institutions underpinning this society-wide process of learning. The epistemic commons is a public resource; these spaces and norms are available to all of us, shaped by all of us, and in turn, also influence the way in which all of us engage in learning with each other. For informed and consensual decision-making, open societies and democratic governance depend upon an epistemic commons in which groups and individuals can collectively reflect and communicate in ways that promote mutual learning.

Inadvertent emotionally or politically -motivated closed-mindedness, manifesting as certainty or overconfidence when dealing with complex indeterminate problems. Epistemic hubris can appear in many forms. For example, it is often demonstrated in the convictions of individuals influenced by highly politicized groups, it shows up in corporate or bureaucratic contexts that err towards certainty through information compression requirements, and it appears in media, where polarized rhetoric is incentivized due to its attention-grabbing effects. Note: for some kinds of problems it may be appropriate or even imperative to have a degree of confidence in one's knowledge—this is not epistemic hubris.

An ethos of learning that involves a healthy balance between confidence and openness to new ideas. It is neither hubristic, meaning overly confident or arrogant, nor nihilistic, meaning believing that nothing can be known for certain. Instead, it is a subtle orientation that seeks new learning, recognizes the limitations of one's own knowledge, and avoids absolutisms or fundamentalisms—which are rigid and unyielding beliefs that refuse to consider alternative viewpoints. Those that demonstrate epistemic humility will embrace truths where these are possible to attain but are generally inclined to continuously upgrade their beliefs with new information.

This form of nihilism is a diffuse and usually subconscious feeling that it is impossible to really know anything, because, for example, “the science is too complex” or “there is fake news everywhere.” Without a shared ability to make sense of the world as a means to inform our choices, we are left with only the game of power. Claims of “truth” are seen as unwarranted or intentional manipulations, as weaponized or not earnestly believed in.

Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowing and the nature of knowledge. It deals with questions such as “how does one know?” and “what is knowing, known, and knowledge?”. Epistemology is considered one of the four main branches of philosophy, along with ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Derived from a Greek word meaning custom, habit, or character; The set of ideals or customs which lay the foundations around which a group of people coheres. This includes the set of values upon which a culture derives its ethical principles.

The ability of an individual or group to shape the perception of an issue or topic by setting the narrative and determining the context for the debate. A “frame” is the way in which an issue is presented or “framed”, including the language, images, assumptions, and perspectives used to describe it. Controlling the frame can give immense social and political power to the actor who uses it because the narratives created or distorted by frame control are often covertly beneficial to the specific interests of the individual or group that has established the frame. As an example, politicians advocating for tax cuts or pro-business policies may use the phrase "job creators" when referring to wealthy corporations in order to suggest their focus is on improving livelihoods, potentially influencing public perception in favor of the politician's interests.

Discourse oriented towards mutual understanding and coordinated action, with the result of increasing the faith that participants have in the value of communicating. The goal of good faith communication is not to reach a consensus, but to make it possible for all parties to change positions, learn, and continue productive, ongoing interaction.

Processes that occupy vast expanses of both time and space, defying the more traditional sense of an "object" as a thing that can be singled out. The concept, introduced by Timothy Morton, invites us to conceive of processes that are difficult to measure, always around us, globally distributed and only observed in pieces. Examples include climate change, ocean pollution, the Internet, and global nuclear armaments and related risks.

Information warfare is a primary aspect of fourth- and fifth-generation warfare. It can be thought of as war with bits and memes instead of guns and bombs. Examples of information warfare include psychological operations like disinformation, propaganda, or manufactured media, or non-kinetic interference in an enemy's communication capacity or quality.

Refers to the foundational process of education which underlies and enables societal and cultural cohesion across generations by passing down values, capacities, knowledge, and personality types.

The phenomenon of having your attention captured by emotionally triggering stimuli. These stimuli strategically target the brain center that we share with other mammals that is responsible for emotional processing and arousal—the limbic system. This strategy of activating the limbic system is deliberately exploited by online algorithmic content recommendations to stimulate increased user engagement. Two effective stimuli for achieving this effect are those that can induce disgust or rage, as these sentiments naturally produce highly salient responses in people.

An online advertising strategy in which companies create personal profiles about individual users from vast quantities of trace data left behind from their online activity. According to these psychometric profiles, companies display content that matches each user's specific interests at moments when they are most likely to be impacted by it. While traditional advertising appeals to its audience's demographics, microtargeting curates advertising for individuals and becomes increasingly personalized by analyzing new data.

False or misleading information, irrespective of the intent to mislead. Within the category of misinformation, disinformation is a term used to refer to misinformation with intent. In news media, the public generally expects a higher standard for journalistic integrity and editorial safeguards against misinformation; in this context, misinformation is often referred to as “fake news”.

A prevailing school of economic thought that emphasizes the government's role in controlling the supply of money circulating in an economy as the primary determinant of economic growth. This involves central banks using various methods of increasing or decreasing the money supply of their currency (e.g., altering interest rates).

A form of rivalry between nation-states or conflicting groups, by which tactical aims are realized through means other than direct physical violence. Examples include election meddling, blackmailing politicians, or information warfare.

Open societies promote the free exchange of information and public discourse, as well as democratic governance based on the participation of the people in shared choices about their social futures. Unlike the tight control over communications and suppression of dissenting views that characterize closed societies, open societies promote transparent governance and embrace good-faith public scrutiny.

The modern use of the term 'paradigm' was introduced by the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn in his work "The Structure of Scientific Revolutions". Kuhn's idea is that a paradigm is the set of concepts and practices that define a scientific discipline at any particular period of time. A good example of a paradigm is behaviorism – a paradigm under which studying externally observable behavior was viewed as the only scientifically legitimate form of psychology. Kuhn also argued that science progresses by the way of "paradigm shifts," when a leading paradigm transforms into another through advances in understanding and methodology; for example, when the leading paradigm in psychology transformed from behaviorism to cognitivism, which looked at the human mind from an information processing perspective.

The theory and practice of teaching and learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners.

The ability of an individual or institutional entity to deny knowing about unethical or illegal activities because there is no evidence to the contrary or no such information has been provided.

First coined by philosopher Jürgen Habermas, the term refers to the collective common spaces where people come together to publicly articulate matters of mutual interest for members of society. By extension, the related theory suggests that impartial, representative governance relies on the capacity of the public sphere to facilitate healthy debate.

The word itself is French for rebirth, and this meaning is maintained across its many purposes. The term is commonly used with reference to the European Renaissance, a period of European cultural, artistic, political, and economic renewal following the middle ages. The term can refer to other periods of great social change, such as the Bengal Renaissance (beginning in late 18th century India).

A term proposed by sociologists to characterize emergent properties of social systems after the Second World War. Risk societies are increasingly preoccupied with securing the future against widespread and unpredictable risks. Grappling with these risks differentiate risk societies from modern societies, given these risks are the byproduct of modernity’s scientific, industrial, and economic advances. This preoccupation with risk is stimulating a feedback loop and a series of changes in political, cultural, and technological aspects of society.

Sensationalism is a tactic often used in mass media and journalism in which news stories are explicitly chosen and worded to excite the greatest number of readers or viewers, typically at the expense of accuracy. This may be achieved by exaggeration, omission of facts and information, and/or deliberate obstruction of the truth to spark controversy.

A process by which people interpret information and experiences, and structure their understanding of a given domain of knowledge. It is the basis of decision-making: our interpretation of events will inform the rationale for what we do next. As we make sense of the world and accordingly act within it, we also gather feedback that allows us to improve our sensemaking and our capacity to learn. Sensemaking can occur at an individual level through interaction with one’s environment, collectively among groups engaged in discussion, or through socially-distributed reasoning in public discourse.

A theory stating that individuals are willing to sacrifice some of their freedom and agree to state authority under certain legal rules, in exchange for the protection of their remaining rights, provided the rest of society adheres to the same rules of engagement. This model of political philosophy originated during the Age of Enlightenment from theorists including, but not limited to John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It was revived in the 20th century by John Rawls and is used as the basis for modern democratic theory.

Autopoiesis from the Greek αὐτo- (auto-) 'self', and ποίησις (poiesis) 'creation, production'—is a term coined in biology that refers to a system’s capability for reproducing and maintaining itself by metabolizing energy to create its own parts, and eventually new emergent components. All living systems are autopoietic. Societal Autopoiesis is an extension of the biological term, making reference to the process by which a society maintains its capacity to perpetuate and adapt while experiencing relative continuity of shared identity.

A fake online persona, crafted to manipulate public opinion without implicating the account creator—the puppeteer. These fabricated identities can be wielded by anyone, from independent citizens to political organizations and information warfare operatives, with the aim of advancing their chosen agenda. Sock puppet personas can embody any identity their puppeteers want, and a single individual can create and operate numerous accounts. Combined with computational technology such as AI-generated text or automation scripts, propagandists can mimic multiple seemingly legitimate voices to create the illusion of organic popular trends within the public discourse.

Presenting the argument of disagreeable others in their weakest forms, and after dismissing those, claiming to have discredited their position as a whole.

A worldview that holds technology, specifically developed by private corporations, as the primary driver of civilizational progress. For evidence of its success, adherents point to the consistent global progress in reducing metrics like child mortality and poverty while capitalism has been the dominant economic paradigm. However, the market incentives driving this progress have also resulted in new, sometimes greater, societal problems as externalities.

Used as part of propaganda or advertising campaigns, these are brief, highly-reductive, and definitive-sounding phrases that stop further questioning of ideas. Often used in contexts in which social approval requires unreflective use of the cliché, which can result in confusion at the individual and collective level. Examples include all advertising jingles and catchphrases, and certain political slogans.

A proposition or a state of affairs is impossible to be verified, or proven to be true. A further distinction is that a state of affairs can be unverifiable at this time, for example, due to constraints in our technical capacity, or a state of affairs can be unverifiable in principle, which means that there is no possible way to verify the claim.

Creating the image of an anti-hero who epitomizes the worst of the disagreeable group, and contrasts with the best qualities of one's own, then characterizing all members of the other group as if they were identical to that image.

Discussion

Thank you for being part of the Consilience Project Community.

0 Comments